2 Related Concepts

2.1 Modern taxonomic classification system

Taxonomic classification system

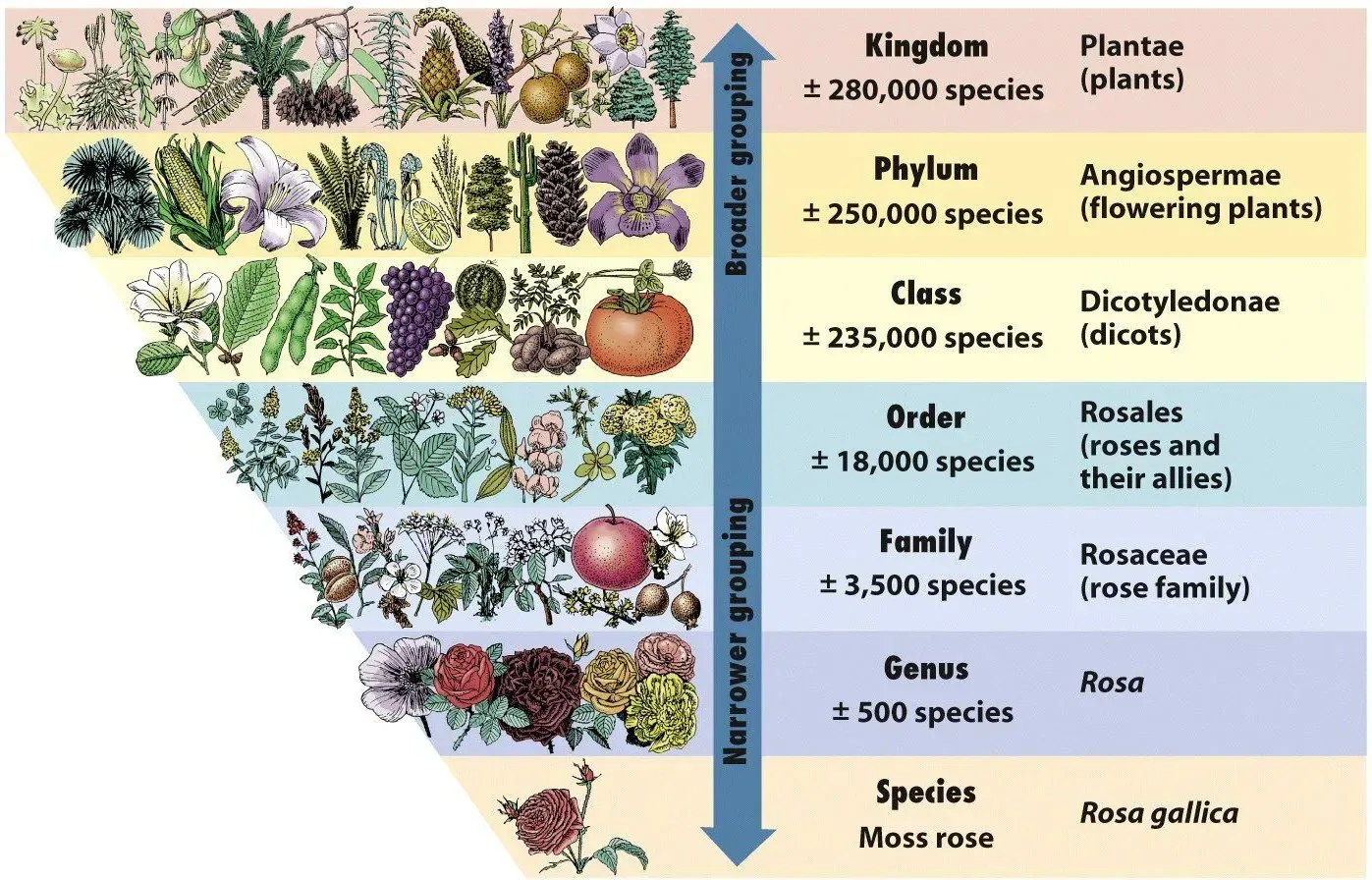

Taxonomy, a methodological approach in the field of biological sciences, refers to the systematic categorization of living entities based on their common attributes. This process organizes these entities into a structured hierarchy of taxonomic ranks, thereby facilitating a comprehensive understanding and study of biodiversity. The internationally accepted taxonomic nomenclature is the Linnaean system, created by Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus[1]. The system is based on the idea that organisms can be grouped into smaller and smaller groups based on their shared characteristics. The modern taxonomic classification system has eight main levels[2]:

- Domain: All living organisms are categorized into three fundamental domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. The plant kingdom falls within the Eukarya domain, distinguished by their eukaryotic cells with a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles.

- Kingdom: Plantae(plants), comprising the vast kingdom of plants, encompasses over 280,000 diverse species. This kingdom encompasses everything from towering Redwoods to delicate mosses, showcasing the remarkable variety of plant life.

- Phylum: Within Plantae, we find the Angiospermae(flowering plants), boasting over 250,000 species. This vibrant phylum is recognized for its characteristic reproductive structure – the flower – which has revolutionized terrestrial ecosystems.

- Class: Roses belong to the class Dicotyledonae (dicots), characterized by seeds containing two embryonic leaves. However, not all flowering plants follow this blueprint. Orchids, for example, belong to the class Monocotyledonae (monocots), bearing seeds with only one embryonic leaf.

- Order: Plants with similar structures and evolutionary relationships are grouped into orders. Order Rosales encompasses roses and their close relatives, sharing specific floral and leaf characteristics. In contrast, Orchidaceae embraces a diverse group of plants, including the mesmerizing orchid family.

- Family: Families represent groups of genera sharing more specific physical and behavioral characteristics than those at higher taxonomic ranks. The Rosaceae family (rose family) encompasses various rose species with similar floral structures and growth patterns. Similarly, orchids belong to the Orchidaceae family, one of the largest families in the plant kingdom.

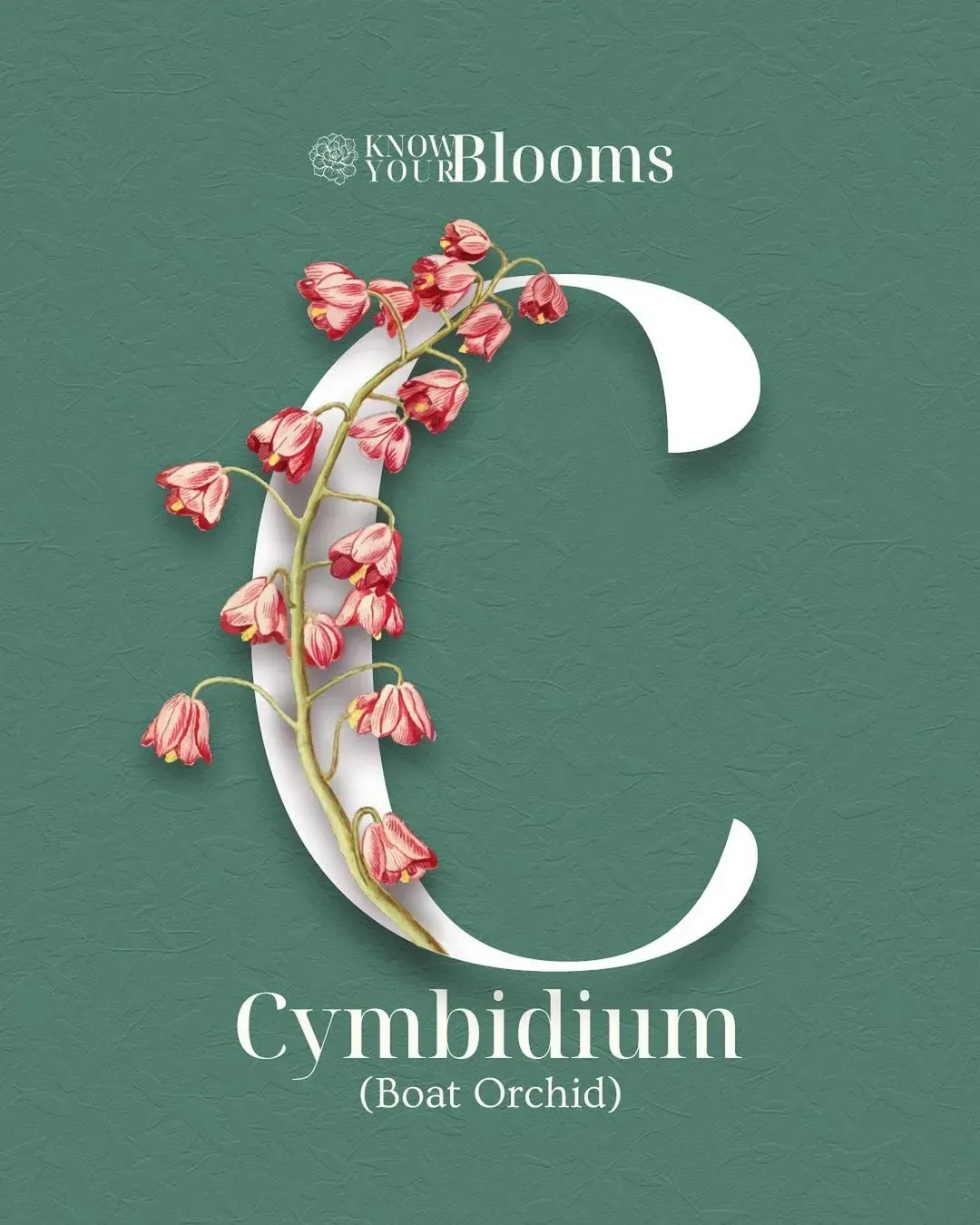

- Genus: Genera represent groups of closely related species that share a recent common ancestor. Rosa, for example, houses all true roses, while the genus Cymbidium encompasses the elegant Chinese Cymbidium orchids.

- Species: The most specific taxonomic unit is the species. A species represents a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. Rosa gallica, the moss rose, exemplifies this concept within the rose family. Likewise, Cymbidium goeringii, a species of Chinese Cymbidium orchid, represents a distinct lineage within its genus.

The eight established ranks of the biological classification system serve as the foundation for taxonomic hierarchy, and are widely used for organizing and categorizing organisms. Nonetheless, in certain groups, supplementary subordinate ranks may be employed to provide a more detailed understanding of the relationships between organisms. For those interested in delving deeper into these ranks and their practical application, I suggest referring to professional texts on plant taxonomy,for example, International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants[3].

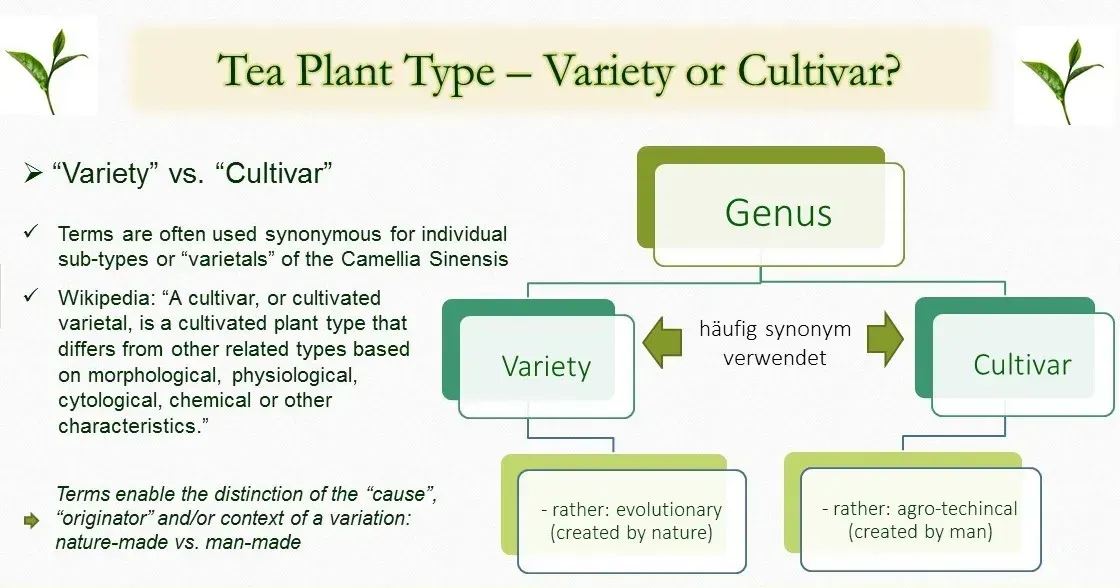

Variant and cultivar

In addition to the eight fundamental levels, the Orchid2024 dataset we offer also includes more nuanced levels than the species level, such as variety and cultivars. A variety is a further classification within a species, representing individuals with naturally occurring unique characteristics. These varieties within a species arise from factors such as geographical isolation, mutations, or adaptation to specific environments[4]. They may exhibit subtle differences in appearance, growth habit, or ecological preferences compared to the "typical" species. However, these differences are often less pronounced than those between distinct species. Essentially, a variety can be thought of as a subgroup within a species, possessing unique traits, yet still capable of interbreeding with other members of the same species.

Cultivars are cultivated of varieties plants that have been selected for specific desirable traits, such as larger fruit, different flower colors, or resistance to disease. Cultivars are not naturally occurring but are created and maintained by humans through selective breeding or other techniques. For example, there are hundreds of apple cultivars, each with its own unique characteristics[5]. In order to maintain the plant’s new feature, the cultivar can only be cloned by taking cuttings, grafting, or tissue culture. Attempts to grow identical plants from the seeds of a cultivar usually result in a plant that reverts to either one of the parents or something completely different than intended.

All cultivars are affiliated with a specific species or its variety. They can be derived from a single species or be interspecific hybrids. So, you can regard cultivar as a more fine-grained unit than speice and variety To recapitulate: Species > Variety > Cultivar. Each level represents a narrower range of genetic diversity and more specific characteristics. Cultivars are the most specific and human-influenced unit, making them the "finest-grained" in this hierarchy.

Here, the term "cultivar" is typically used in the context of plants, specifically cultivars. Strictly speaking, cultivars do not exist in the same way for animals. However, there are some concepts related to animal breeding that share some similarities with cultivars. Breeds: Like cultivars, breeds are distinct populations of animals within a species that share specific physical or behavioral characteristics. They are created and maintained through selective breeding, where animals with desired traits are mated to produce offspring with those same traits. Examples include dog breeds like Labrador Retriever or Poodle, or cattle breeds like Holstein or Angus.

The Orchid2024 dataset is a comprehensive collection of Chinese Cymbidium orchid images. It encompasses over 1,200 cultivars across 8 species and their variants. However, given the widespread cultivation of Chinese Cymbidium orchids, there may be additional cultivars and numerous hybrids not yet included in the dataset. I am actively seeking to expand the dataset to include these cultivars.

Naming Plant Species, Varieties, and Cultivars

The rules for naming plant species, varieties, and cultivars are guided by the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP)[6]. Botanical nomenclature is the body of rules for determining which name applies to a particular taxon, and occasionally if a new name is needed. Modern botanical nomenclature started with Carl Linnaeus and his 1753 publication, Species Plantarum (Latin for "The Species of Plants"). It is now governed by the ICNCP. This code provides regulations for naming cultigens, plants whose origin or selection is primarily due to intentional human activity. Let's delve into the world of plant names refering the picture below:

Species: Each species has a unique scientific name consisting of two parts(Latin Binomial), the genus (first, capitalized) and the specific epithet (second, lowercase), representing the basic unit of scientific classification. (Example: Cymbidium goeringii is the species name, "Cymbidium " is the genus and "goeringii " is the specific epithet.) Regardless of language or region, this scientific name identifies the species precisely. In the horticulture industry, Cymbidium often omitted as C. or Cym.

Varieties(Infraspecific Rank and Name): Sometimes there may be variants in certain species. So, varieties are denoted by the species name followed by "var." and the variety name, in italics. For example, Cymbidium goeringii var. longibracteatum can be used to denote a variety(variant species) of Cymbidium goeringii.

Cultivar: Each cultivar possesses a unique epithet that is distinct from the species and variety names. However, not all plants have a cultivar name. This depends on whether there exists a collection of plants that have been selected and cultivated for their particular, distinct, uniform, and stable attributes. These names are enclosed in single quotation marks. At times, cultivar names are registered with international or director authorities and must adhere to specific rules regarding length, format, and uniqueness, so that the name becomes officially recognized and protected, ensuring no other cultivar can be named the same. If a cultivar is not registered, it is typically named according to the customs of the plant industry. For instance, many cultivars of Chinese Cymbidium orchids are not registered. In such cases, I opt for a common rule: using the Pinyin of these flowers’ Chinese names as their cultivar names.

Common Name and the Trademark Name: Common names are informal names used by the general public. Occasionally, nurseries develop and trademark cultivar names to make them more marketable[7]. These names can often be omitted.

Some questions about flower names

Reading this, you may be confused. When we discuss various flowers, are we referring to a vibrant tapestry of species, a specific genus, or perhaps an entire floral family? If an individual casually mentions their appreciation for the beauty of various flowers, they might be using the term in a broad sense to include all types, encompassing different species, genera, and families.

The level of detail we’re addressing can fluctuate based on the context and the aspect we wish to highlight. For instance, if we’re discussing the unique features of a specific flower, like the climbing habit of clematis, the species is most relevant. If we’re comparing the petal structure of different lilies, the genus might be a more suitable level. And if we’re discussing the fruit development of plants with fleshy fruits, the family could be the appropriate level. To circumvent confusion, it’s always beneficial to provide additional information or clarify the level of detail when discussing flowers. For example, The terminology we use for phalaenopsis, roses, and orchids depends on the context and the level of detail we wish to communicate:

Phalaenopsis:

- Genus: This is the most precise term because "phalaenopsis" refers to a specific genus of flowering plants within the larger orchid family.

- Species: There are about 70 species within the Phalaenopsis genus, so using the term "phalaenopsis" could technically refer to any of these individual species, but without further clarification, it would be ambiguous.

- Family: Saying "phalaenopsis" is not accurate at the family level. Phalaenopsis belongs to the Orchidaceae family, so if you want to emphasize the broader group, Orchidaceae family,would be the appropriate term.

Roses:

- Genus: "Rose" can denote the genus Rosa, which encompasses hundreds of species with diverse characteristics.

- Species: Specifying a particular rose species like Rosa chinensis (China rose) or Rosa damascena (Damask rose) provides more accurate information.

- Family: Roses belong to the Rosaceae family, but simply saying "rose" wouldn’t imply this level of classification.

Orchids:

- Family: "Orchid" refers to the entire Orchidaceae family, one of the largest and most diverse plant families, containing over 880 genera and 26,000 species.

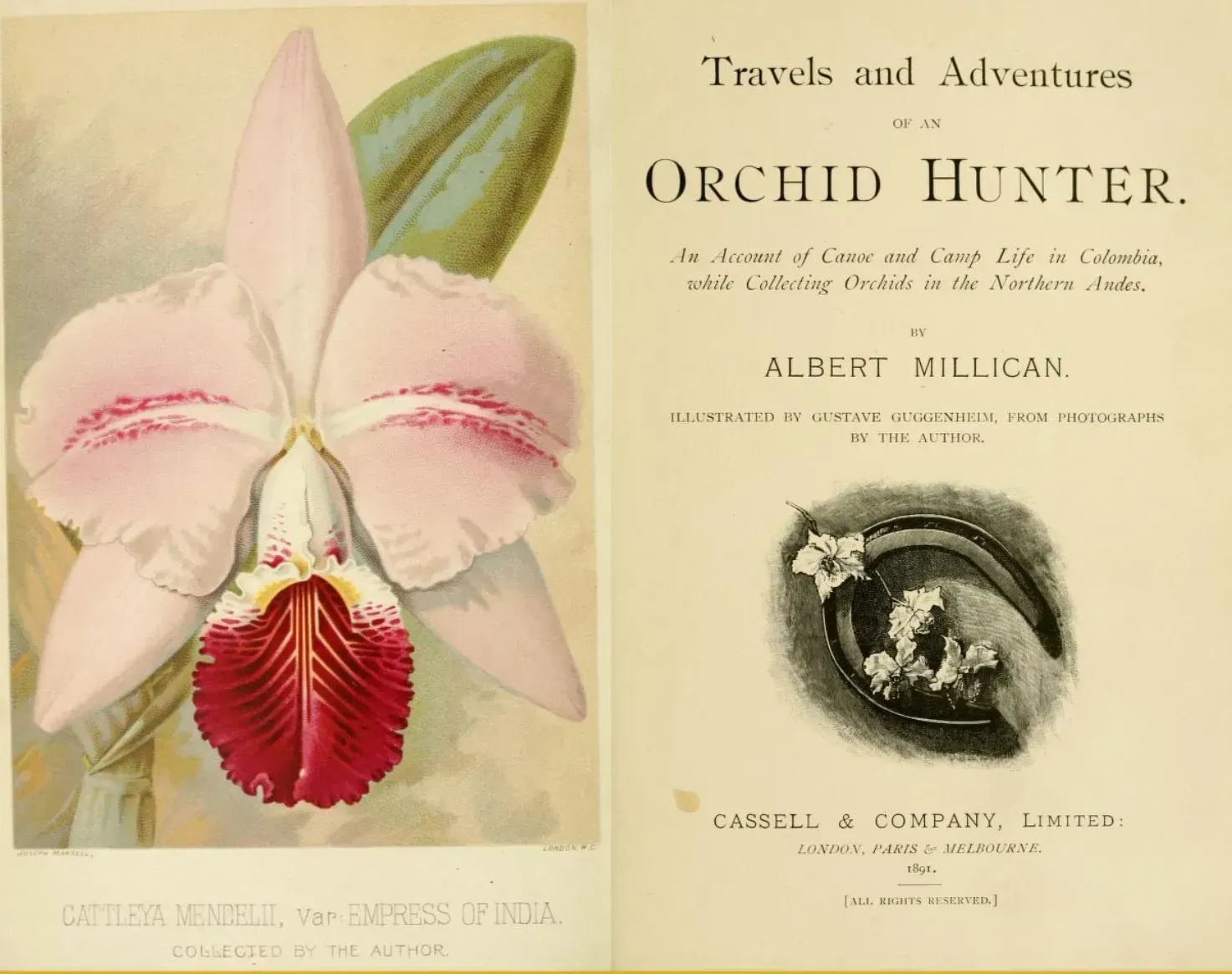

- Genus: Saying "orchid" doesn’t specify a specific genus within the family. Phalaenopsis, Cattleya, Dendrobium, and Cymbidium are just a few of the numerous orchid genera.

- Species: As with roses, mentioning a specific orchid species like Phalaenopsis amabilis or Cattleya walkeriana is the most precise way to identify the plant.

In conclusion, the appropriate term depends on the context and the level of specificity required. If the information source isn’t explicitly referring to a particular species or family, attributing it to a genus is less prone to error. When there’s ambiguity, it’s indeed safest to assume the term refers to the genus, as it’s a middle ground between the broadness of a family and the specificity of a species.

2.2 Relevant concepts of orchid names

Orchids, scientifically known as Orchidaceae, encompass all plants within the orchid family. This diverse and widespread group of flowering plants is renowned for their colorful and fragrant blooms More specifically, the term ‘orchids’ is often used to denote those types of orchid plants that are widely recognized by horticulturists and enthusiasts for their ornamental value[8]. This includes a multitude of varieties that have been selectively bred and cultivated from orchid plants. This means that the specific flower someone might picture when they hear "orchid" can vary greatly depending on their region and cultural background. Here are some examples:

Tropical Regions

In countries like Singapore, Thailand, and Brazil, where orchids are abundant and often native, the term most likely refers to epiphytic orchids that grow on trees and branches. These orchids come in a dazzling array of shapes, sizes, and colors, with some popular examples being Cattleyas, Phalaenopsis (Moth Orchids), and Dendrobiums. For example, Phalaenopsis amabilis is the national flower of Indonesia [9], Vanda 'Miss Joaquim' is the national flower of Singapore [9:1], In the Americas, several countries, including Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Belize, Costa Rica, and Guatemala, have chosen orchid varieties that thrive in their respective regions as their national flowers[9:2].

Most of the cultivated orchids are epiphytes. They do not grow in the ground but instead grow in trees or on rocks. This puts their roots out into the air rather than underground[10]. The word "epiphyte" (EP-ih-fite) means "air plant" or literally "to grow upon a plant". Epiphytes are not parasites. They do not take anything from the host plant. Epiphytes perch upon other plants but get their moisture and nutrients from air, rain and debris.

Temperate Regions

In Europe, North America, and parts of Asia, where the climate is cooler, "orchid" often refers to terrestrial orchids that grow on the ground. These orchids tend to be less flamboyant than their tropical counterparts, but they still offer delicate beauty and fascinating adaptations. Common examples include Paphiopedilum(Lady Slippers), Cymbidiums, and Bletillas. In the 19th century, during the Victorian era in England, Paphiopedilum was highly sought after by orchid growers in Europe and America, causing it to become very rare in the wild due to over collecting[11]. Bletilla orchids are amongst the easiest of all orchids to grow and were one of the earliest exotic orchids imported into Europe[12]. Cymbidium orchids are among the oldest horticultural orchids in the world, which is distributed in tropical and subtropical Asia (such as China, northern India, Japan, Malaysia, and the Philippines) and Australia.They have decorative flowers spikes and are one of the least demanding indoor orchids[13].

Cymbidiums, Bletilla, Cypripedium, and Orchis, etc. are terrestrial, which means "growing in the ground". Most of the native orchids of Chinese, the United States and all the natives of Europe are terrestrials. Some epiphytic orchids have adapted to growing on rocks because nearby forests may not offer enough light. Rock-growing orchids are known as lithophytes.

Specific Regions

In China, the term "orchid" traditionally refers to the Chinese Cymbidium Orchids, which are native to the country. However, there is another category of orchids known as "Exotic Orchids" in China[14]. This term was initially used to describe orchids that were extensively cultivated abroad and later introduced to China. These include a variety of species such as Phalaenopsis, Cattleya, Vanda and Dendrobium. These orchids are known for their large, colorful flowers and their cultivation methods significantly differ from those of traditional Chinese Cymbidium Orchids. Over time, the term "Exotic Orchids" has evolved to refer to all orchids with showy flowers, regardless of their true place of origin or whether they are cultivated abroad or in China. Interestingly, some species that are actually native to China, such as Paphiopedilum armeniacum and Paphiopedilum malipoense, are also commonly referred to as exotic orchids. This is due to their ornamental characteristics and unique cultivation techniques, despite them being authentic Chinese orchids.

2.3 A brief history of orchids and cymbidiums

History of orchids

The exact origins of orchid cultivation remain shrouded in mystery. Its purpose, whether purely aesthetic, medicinal, or a beautiful blend of both, is equally unclear. The earliest documented mention can be traced back to the mythical Chinese ruler Shennong, whose "Divine Farmer's Herb-Root Classic" extolled the medicinal virtues of Dendrobium orchids[15]. Confucius (551-479 B.C.) further cemented the flower's cultural significance by admiring its captivating fragrance.

The etymology of the English word "orchid" can be traced back to Ancient Greece. The term is derived from the Greek word "orchis" which translates to "testicle." This association was made due to the resemblance of the root tubers of certain orchid species, particularly those in the Orchis genus, to a pair of testicles. In his work "Inquiry into Plants" written around 300 BC, Theophrastus, a student of Aristotle, used the term "orkhis" to refer to some terrestrial species of orchids which gave origin to the name of the whole family "Orchidaceae"[16]. Over time, the term "orchis" evolved into the Latin "orchidea," and eventually into the English "orchid" that we use today. In 1737, Carl Linnaeus first used the word Orchidaceae to designate plants with similar features[17]. In 1830, John Lindley (botanist and taxonomist) did the first classification of orchids[18]. He wrote many books about plants but it was his studies about orchids, The Genus and Species of Orchidaceae Plants, that made him well known.

Thereafter, Victorian Great Britain, roughly spanning 1837-1901, saw a great surge in exploration and interest in exotic natural treasures. Orchids, with their diverse and often dazzling blooms, captivated Victorian sensibilities[19]. This fascination spurred the rise of "orchid hunters. These hunters faced dangers like extreme weather, wild animals, and even hostile indigenous tribes. The discovery of new orchid species sparked a craze known as "orchid fever." Collectors, both individuals and institutions, became obsessed with acquiring the most unique and valuable specimens. Prices for certain orchids soared to astronomical heights, with a single plant sometimes fetching more than a house! Unfortunately, this fervent pursuit of orchids had tragic consequences. Driven by greed and ambition, some hunters resorted to extreme and reckless measures. They plundered entire habitats, often leading to the depletion of rare orchid species. Additionally, the harsh conditions and demanding physical challenges of expeditions resulted in the deaths of numerous orchid hunters.

If you want to delve deeper into this captivating topic, "Orchid Fever: A Horticultural Tale of Love, Lust, and Lunacy" by Eric Hansen: This book delves into the history of orchid collecting and the human drama behind the "orchid fever" phenomenon[20].

Today, international trading of orchids harvested in the wild is banned by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) adopted in 1973[21]. However, many orchid species are still endangered, and orchid smuggling is thought to contribute to the loss of some species of orchid in the wild.

History of cymbidiums

Cymbidiums are among the most ancient horticultural orchids worldwide. These plants have a rich history, particularly in China, which is recognized as one of the first countries to cultivate Cymbidiums[22]. Cymbidiums are known for their large, beautiful flowers that come in a variety of colors, including white, yellow, pink, green and red. They can be single or double, and often have a pleasant fragrance. Cymbidium's long-lasting flowers have made Cymbidium varieties and hybrids some of the most commercially valuable orchids in the world's floriculture industry[23]. With proper care, they can keep in a vase for several weeks.

The Cymbidium genus, a member of the Orchidaceae botanical family, was first officially characterized in 1799. This formal description was provided by Olof Swartz, a Swedish botanist, who detailed the unique attributes of these orchids[24]. He named them "little boats", inspired by the bowl-like shape of the lower petal, also known as the labellum. The word Cymbidium is derived from the Greek word "kymbos", which means "boat". The lip of the flower looks a bit like a boat which is how the Cymbidium gets its name. Therefore, Cymbidium is also commonly known as boat orchid.

Thereafter, Cymbidiums began to gain recognition in Europe, particularly during the Victorian era, when their exotic charm captivated flower enthusiasts. The dawn of the 20th century marked the arrival of the first Cymbidium imports from the Himalayas to England, which signified the start of their popularization as cut flowers[25]. Breeders began to crossbreed these plants, gradually producing more varieties and colors. Today, Cymbidiums continue to enjoy worldwide popularity, especially in China. Different cultivars of Cymbidium are available all year round, peaking in autumn and winter.

Reid, Gordon McGregor. "Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778): His life, philosophy and science and its relationship to modern biology and medicine." Taxon 58.1 (2009): 18-31. ↩︎

Schuh, Randall T. "The Linnaean system and its 250-year persistence." The Botanical Review 69.1 (2003): 59-78. ↩︎

Turland N J, Wiersema J H, Barrie F R, et al. International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017[M]. Koeltz botanical books, 2018. ↩︎

Cultivar versus Variety. hortnews.extension.iastate.edu/2008/2-6/CultivarOrVariety.html. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Cultivar. biologydictionary.net/cultivar. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Spencer, Roger D., and Robert G. Cross. "The international code of botanical nomenclature (ICBN), the international code of nomenclature for cultivated plants (ICNCP), and the cultigen." Taxon 56.3 (2007): 938-940. ↩︎

Naming Plants. www.bcarboretum.org/plants/nomenclature. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Orchid. www.britannica.com/plant/orchid/Structural-diversity. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

List of nation flowers. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_national_flowers. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Epiphyte or Terrestrial?. www.aosforum.org/newsletters/pages/aug09.html. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Paphiopedilum insigne. www.wikiwand.com/en/Paphiopedilum_insigne. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Bletilla. www.irishorchidsociety.org/orchids/bletilla-2/. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Cymbidium Orchids. www.abc.net.au/gardening/how-to/cymbidium-orchids/9426288. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Chinese and Exotic Orchids. www.mikeparkbooks.com/product/29322/Chinese-and-Exotic-Orchids. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Rahman, Minhajur, et al. "Uncovering the Phytochemical Profile, Antioxidant Potency, Anti-Inflammatory Effects, and Thrombolytic Activity in Dendrobium lindleyi Steud." Scientifica 2023 (2023). ↩︎

Bulpitt C J. The uses and misuses of orchids in medicine[J]. Qjm, 2005, 98(9): 625-631. ↩︎

Anghelescu, Nora Eugenia DG, et al. "A history of orchids. A history of discovery, lust and wealth." Scientific Papers. Series B. Horticulture 64.1 (2020). ↩︎

A Bit of the Orchid's History. sites.millersville.edu/jasheeha/webDesign/websites/OOroot/history.html. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

The Dangerous and Highly Competitive World of Victorian Orchid Hunting. www.mentalfloss.com/article/88888/dangerous-and-highly-competitive-world-victorian-orchid-hunting. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Hansen, Eric. Orchid fever: a horticultural tale of love, lust, and lunacy. Vintage, 2000. ↩︎

Hinsley, Amy, et al. "Estimating the extent of CITES noncompliance among traders and end‐consumers; lessons from the global orchid trade." Conservation Letters 10.5 (2017): 602-609. ↩︎

All about cymbidium orchidhistory. littleflowerhut.com.sg/flower-guide/all-about-cymbidium-orchid-history-meaning-facts-care-more/. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Balilashaki, Khosro, et al. "Biochemical, cellular and molecular aspects of Cymbidium orchids: an ecological and economic overview." Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 44.2 (2022): 24. ↩︎

Yukawa, Tomohisa, and William Louis Stern. "Comparative vegetative anatomy and systematics of Cymbidium (Cymbidieae: Orchidaceae)." Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 138.4 (2002): 383-419. ↩︎

Origin and symbolism. cymbidium.info/en/home/symbolism-and-history/. Accessed 1 Jan. 2024. ↩︎